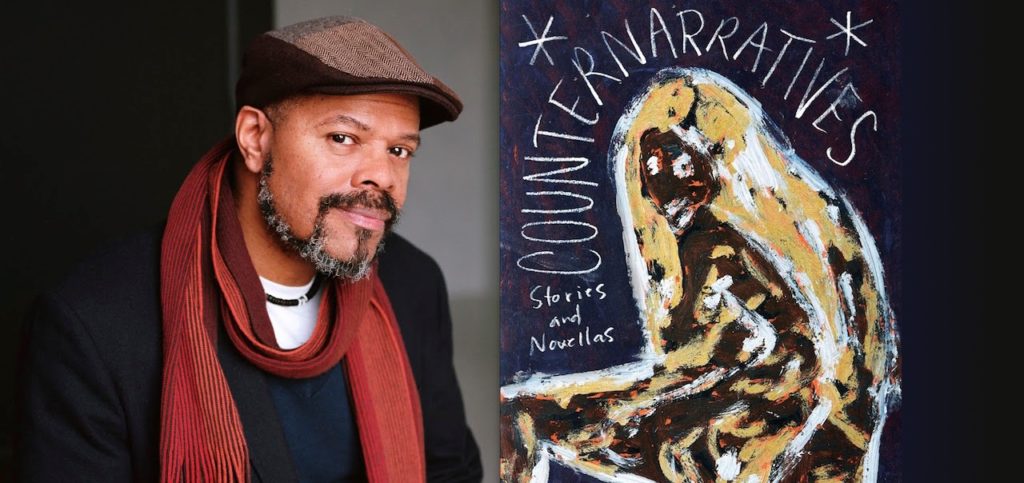

John Keene is a Distinguished Professor of English and African-American and African Studies at Rutgers-Newark, where he has served as the chair of the African-American and African Studies department since 2015. In his own words, he says, “I’m a writer, a translator, an artist, an editor, and a mentor.” He is affiliated with organizations including Cave Canem, where he has served as a fellow, and the Dark Room Writers Collective, which he joined several years after obtaining his undergraduate degree at Harvard University. He is currently a board member of the African Poetry Book Fund, which aims to make available works by poets from the African continent and was founded by Kwame Dawes and is based at the University of Nebraska. He is also a recipient of the MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, which he was awarded in 2018.

Widely celebrated as an experimental writer, John has published two collaborative volumes of poetry, including Seismosis (2006) and GRIND (2016), a chapbook of poems called Playland (2016), and translated the Brazilian author Hilda Hilst’s novel Letters from a Seducer from Portuguese. His first novel Annotations was published in 1995, and his short story and novella collection Counternarratives (2015) was lauded to wide acclaim.

I’m a writer, a translator, an artist, an editor, and a mentor.

Monique Ngozi Nri: I’m curious what your take is on the Amanda Gorman poem that she read at the inauguration on January 20.

John Keene: I want to begin by saying that I honor her as a young poet. I encourage people to read poetry. I encourage people to write poetry, and above all, to listen to poetry and sit with poems. I think what was very clear to me is that her poem comes out of several different traditions and that these are probably not the traditions that are being regularly taught in colleges and universities.

On the one hand, we just had a fascist insurrection. We have state murders of Black people. We have the continued dispossession of indigenous people. I understand the criticism that some people may have that delivering a poem on behalf of any administration that is going to pursue empire is problematic—whatever the political party.

On the other hand, I do think the new administration is going to be better in some key ways than the former administration, which had to be dragged out kicking and screaming, and I do celebrate this young poet. She is quite talented.

MNN: Looking at the second and third stories in Counternarratives and your description of the dynasties of enslavement and slave owners, I think it’s an ironic twist that you put on some of the statements that you make about how these people think about themselves in relation to what they’re doing to people of African descent. I was struck by the first story. It reminded me of The Kingdom of This World in the sense that it was an in-depth look at the life or the experience of this particular man.

I wondered why you chose to place that story at the beginning of the book, and if you could talk a little bit about the idea of making that story, our story, available and present for people to encounter.

JK: I would say that with “Mannahatta,” I was very interested in thinking about a counter-history in terms of the United States’ origins. That’s not to suggest that “Mannahatta” stands as a kind of founding statement; the U.S.’s founding by its very nature is problematic. I wanted to think through and write the story of someone who arrived very early, who was not indigenous, who was a mixed-race person from the new world but also a product of the old world, whose goal was not to be a settler colonialist or an extractive colonialist. Juan Rodríguez (Jan Rodrigues) was a real historical figure. When he arrives in what becomes Manhattan, what becomes New York City, he is engaging in trade, but his idea is not “I’m going to lay claim to this world” but rather, “I want to become a part of it.”

He wants to separate himself from the Dutch colonialists on whose ship he’s working. I was fascinated by this idea of a figure whose originary presence is right in front of us and, at the same time, remains so obscure. Several organizations and one of the departments at CUNY have honored him; they created a plaque for him, and they had a full ceremony for Rodríguez. But he remains utterly obscure, even to New Yorkers.

It’s fascinating in the sense that he was apparently born in Santo Domingo, and New York has one of the largest populations of Dominican-Americans and, as a city, has one of the most sizable populations of Latinx people in the U.S. Among U.S. cities, New York has had and still has the largest numerical population of people of African descent in the entire United States. One would think that there would be, even if not regular celebration, at least more discussion of someone like Juan Rodríguez.

His story challenges the narrative that we have been handed down about the origins of this country—and what might have been and what became possible. I think it’s very important that, so early on, this Black figure, this mixed-race, non-English-speaking figure, was there at the beginning. This was around 1613—a few years before when “The 1619 Project” commences. I say this not to erase “The 1619 Project,” but to underscore that histories are complex.

Of course, we know there were people of African descent who arrived with the Spaniards, etc. It was very important for me to use that as a thematic and metonymic starting point for the collection because it both grounds us in this idea of what U.S. American history is and opens up spaces of possibility for thinking in broader hemispheric and global terms.

Peter Soucy: The title of “Mannahatta” shares its title with Walt Whitman’s poem “Mannahatta.” We recently spent a semester learning about Walt Whitman, him being racist, and his view of America totally overshadowing Black and indigenous people’s history: a view of a united America but only for white people. How much do you see your story as an inverse of this narrative?

JK: That was certainly in my thinking. On the one hand, Whitman is really one of the greatest and most influential American poets—not just for American literature but also for literature all over the globe. His influence extends in all directions. On the other hand, you’re right. Whitman, like most White people of his generation and preceding and subsequent generations, could be extremely racist. He had a pretty hypocritical idea about a kind of brotherhood of White people which, interestingly enough, you see animating the pre-Civil War period: this clash between the Union and Confederacy, and then afterward. As the country is reuniting, one understanding is that what is really being reunited is whiteness and white social capital and power. Power in exchange for throwing Black people under the bus and stripping away their rights. Northern capital can do what it wants to do. This is a kind of recurrent theme.

To go back to Monique’s question, one of the things I did not mention but relates directly to this idea of the uniting of whiteness is this question of capital—in all its forms: social, political, economic, cultural, etc. What does it mean that the Dutch viewed Manhattan or Mannahatta primarily as a trading post? I wanted to try to think through another way into our past, our understanding of capitalism—to think about how this character views what he’s doing in terms of trading and engaging in commerce of various kinds with the indigenous people.

In a sense, the title is both an ironic criticism of Whitman and also an invocation of him. One of the things that happens in that story, as we see so often in Whitman, is his really remarkable invocation of the rivers surrounding New York. You think about “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” Whitman’s famous poem. I tried to make sure that one of the first things that Juan Rodríguez sees is the East River, but he also sees Long Island, which includes Brooklyn. That’s what he views on the other side of that shimmering river as he sees this other world of freedom. He’s part of this new world, this other world. He can see its expansiveness, but his desire is not to own it, to dominate it, but to walk through that window into another life in which he might live harmoniously with this new world and become part of it.

Elizabeth Hickson: You mention the idea of this new world that is an “other world,” and I started thinking of conceptions of translation—of strangeness, a thing and its other. How does your translation work relate to that idea, and how does translation theory influence your writing in general?

JK: One of the things that I’m thinking about is Édouard Glissant’s idea of relation and opacity. Related to that is the question: What does it mean to live with and not to dominate? What does it mean to be together without being the same—to fully accept the idea of difference and all its difficulty and pain and complexity, and to be in a continuous conversation about that? When I think about translation, that is one of the things that has profoundly influenced my work.

I find that, whenever I translate or read translations, it transforms my sense of what’s possible in a good way.

MNN: I was struck that part of your work with Kwame Dawes and the African Poetry Book Fund involves bringing actual African poets into print or reprinting their work. I feel that that is an area that, even for myself, is relatively unexplored, and I’m Nigerian/Barbadian. Can you talk a little bit about the importance of those translations, and the importance of that work for our understanding as a whole?

JK: One thing that becomes clear when you look at the work of poets who have not been so appreciated, whose work has been reissued as selected poems or collected poems, and work that has not really been in English or even in a European language is that it changes your understanding of history, of literary history, of aesthetics.

I find that, whenever I translate or read translations, it transforms my sense of what’s possible in a good way. I think there’s a way in which it brings a centrifugal quality to the conversation, particularly in mainstream American “elite” circles about literature.

MNN: If you take “On Brazil,” in this passage where Londônia is about to testify, the way that this voice describes the scene reminds me very much of what we’re going through now with the trial of Trump, and this kind of split perception as to what is going on:

“Despite the seriousness of the affair, a current of easy familiarity passed among the men. Several laughed at Londônia’s account of the circular march through the jungle.”

What is your intention with speaking with that voice? Because at some points, I just laughed out loud.

JK: I would say: I want you to laugh. There are actually several places throughout Counternarratives where some of my intention was to be funny, but in a very wry, ironic way. In that passage that you cite, my goal was to lay bare how power works. You have the indigenous people who were the targets of this marauding party from the empire. And you also have this African Quilombo, where people escaped chattel slavery.

Both the story’s protagonist the Colonel himself—and the people around him—and the person arguing from the other side who is opposing him are still part of power. They’re just different annexes of power; they’re up against each other, but depending on where you sit in the hierarchy, as is the case with the Londônias-Figueiras family, the Colonel has so much more power. It does not matter how beautiful the arguments on the other side are. This is how power works.

He knows he’s not going to be punished harshly for genocide: the outright killing and slaughtering of people. Of course, this is justified under the ideology, the ethos, the morality, the ethical structure, and the society in which he lives. They have created a space or place for this: to seize land, to seize power, to kill people. I wanted to think about: Usually, if you’re a historian, when a voice or voices are recounting things, there’s a way that you’re going to do this. Your own perspective is going to enter, but with great care. Your prose is going to be shaped by the way that you think about the archive you’re exploring and whose materials you’re working through.

I wanted to be much more overt in this story: to bring in a range of discourses, an array of voices, that keep disrupting or destabilizing any easy understanding of how to see or read or think about what’s going on.

MNN: It’s also fascinating to me that at no point in the story, “An Outtake” is it discussed that the story’s protagonist Zion is the so-called master’s child. What are the pieces that you’re putting in the narrative to break up assumptions about what stories should look like or have looked like?

JK: You’re one of the rare people who has noted that Zion was thought to be the son of Mr. Wantone. That goes right over people’s heads. We know about Zion’s mother. In a sense, we know about his surrogate mothers and the people around him: his family, the constructed family. We hear very little about his father. This was one of the first stories in Counternarratives that I wrote. I was fascinated by this idea of what the German literature scholar Andres Huyssen calls “analytical fiction.”

Huyssen, when speaking about the German writer Alexander Kluge, raised questions about how you engage the reader critically yet so that they keep reading to the end. You include these critical aspects that defamiliarize. How do you zoom in? How do you zoom out? I don’t mean just in a technical sense, but I mean in terms of critique.

I was particularly fascinated with this idea of slavery and the American Revolution. When I think about most discussions of the American Revolution, even today, slavery is there but [not really]. I think about the popularity of Hamilton. As my colleague Lyra Monteiro at Rutgers-Newark and other people have pointed out: If Hamilton really looked at that moment in time and Alexander Hamilton himself, etc., we’d probably have a very different musical. Other people would have come to the fore. It’s fascinating.

Of those main figures, the one who was not a slave owner and was no fan of slavery was John Adams. He’s basically not part of Hamilton. That’s not to criticize Lin-Manuel Miranda, but to say with regard to the character Zion, slavery, and Massachusetts: What does it mean to think about the place of someone so radically unfree at the very moment when and in one of the very places where the rhetoric of freedom is so powerful. The thing about Zion is: He’s not a noble character, but he is an emblem of radical freedom. He does not feel that any rule of law, and especially the dominating structure—that brutal, oppressive, dominant structure of chattel slavery—should constrain him. However, there is no space or place for someone like him at all in this world.

I wanted to be much more overt in this story: to bring in a range of discourses, an array of voices, that keep disrupting or destabilizing any easy understanding of how to see or read or think about what’s going on.

EH: I wonder if this concept of radical freedom is something you’re actively thinking about as you write. Is genre something you’re thinking about, or do you apply this idea of radical freedom toward the very idea of writing itself?

JK: I’ve been writing poetry and fiction, poetry especially, going back to childhood. I wrote fiction and poetry when I was in high school and college as well. I think I’m very aware of the traditions that I’m writing out of, though, I try as much as possible not to censor myself when I’m writing. Now that I’m older, I have a clearer sense, when I start writing, of what it is I’m doing.

With the exception of one book I published a few years ago with Nicholas Muellner (GRIND), which is a wonderful collaboration, every other book that I’ve published I’ve encountered some challenges getting them published. I think it’s very important as a writer—and I say this especially to student writers, apprentice writers, emerging writers—to be as open and free as you possibly can when you’re writing.

PS: Do you think you would be able to create the same kind of points or get across what you’re trying to say if you weren’t allowed to fictionalize, or is that balance between fiction and nonfiction important?

JK: I think about so many writers like Kiese Laymon, Eula Biss, etc., who have taken really fascinating and provocative routes with nonfiction. However, I’m personally interested in the possibilities of fiction as a genre.

Well before autofiction became a hot genre in the 2000s, I published Annotations. There are so many different works that inspired it. Clearly the very obvious ones: works by Lyn Hejinian, Ntozake Shange, Samuel Delaney, Clarence Major, and other people I mention in the book itself, as well as people I didn’t mention, like Kathy Acker who I was reading at the time. Annotations comes almost 20 years after Serge Doubrovsky coined the term “autofiction,” but I still think there are so many interesting things one might do with that line between fiction and nonfiction, particularly on the fiction side.

A few years ago, I taught Anelise Chen’s So Many Olympic Exertions. I also taught Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be? and Chris Kraus’s Aliens and Anorexia, among others. Each could be viewed as nonfiction, as memoirs, but each also functions as a novel. When I read Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel Americanah, I thought it was so fascinating to see an aspect of the world that I inhabit portrayed as fiction. Of course, her perspective is different than my perspective; she’s Nigerian-American, and I’m African-American. But in so many ways, there were these powerful moments of recognition.

I am trying to consciously think, “What does fiction do? Why do we write fiction? Why do I write fiction? What are fiction’s possibilities, particularly now?” I think about the extraordinary power of narratives. If nothing else, the QAnon conspiracy should make anyone who is working with narratives raise the question of: “What is it about particular narratives that make them so compelling, so galvanizing, so mesmerizing that they become the means to explain anything and everything?”

They can be extremely dangerous. I hope that we think more about narrative and its power because it is extraordinarily powerful when it comes to human beings and the ways we understand the world. We live in narrative. We construct narratives. We are the products of narratives. We organize our lives in and as narratives. The narratives that we create are going to be particularly important now. We see how important narrative is for even just the very idea of what we call democracy or society or our ability to live on a globe that is increasingly endangered. Everything is shaped by narrative.

MNN: You mentioned the Dark Room Collective and Cave Canem in terms of being a fellow. What place does community play in your existence as a writer?

JK: I teach at a university, so I have an amazing community of colleagues who are writers and scholars, students, staff, and people I work with. It’s very invigorating. They keep me thinking and dreaming. I also think about the larger community of writers and different communities of writers that I’m part of.

When I was starting out, the Dark Room was particularly important because it was a group of primarily young Black writers, as well as artists, musicians, and filmmakers, who were not part of an established institution. We had to create our own thing, if not an institution, then our own space for the kind of work we wanted to see, the kind of writers we wanted to learn from, and the kind of community we wanted to bring into the world.

Of course, I also think about the old OutWrite conferences, which were an invaluable space where LGBTQ+ writers came together when the AIDS pandemic first hit. I think of Fire & Ink and how it has brought together Black LGBTQ+ writers.

I think communities are very important, especially for writers. When you’re working independently for so much of your time, having a community or communities that you can share your work with, bounce ideas off of, and transform the world with is incredibly important.

EH: I’m wondering if there’s anything you’re working on now that you’d be willing to share with us.

JK: I’m working on several projects, but I do have a book of poetry, titled Punks, which is scheduled to appear in November from The Song Cave, so I’m working on that. I also have some long-form fiction projects that I’ve been working on for a while.

There is also a wonderful anthology that Kevin Young just edited: African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle and Song. That’s a marvelous gathering of work, and I’m very happy to say—thanks, Kevin!—I have some work in there too that’s quite formally experimental. That’s a volume where you get to see a really extraordinary range—and you see the richness and depth and history.

All around us, people are dying. So many of them are elderly, so many of them are Black and brown…The question is: How do you make sense of that? How do you write about that?

MNN: Has your writing been affected by the pandemic at all?

JK: As you all know, being in the New York metro area was terrifying back in March, April, and May of 2020. It was a terrible situation in the city and New Jersey. It’s almost unnerving to think that, as bad as things were in New York and New Jersey last spring, it eventually became that way pretty much all over the United States now. Truthfully, the past administration’s neglectful, incompetent non-handling, and mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic, to me, was just another example of a kind of war on the American people, or sectors of the American people.

I lived through the AIDS pandemic, particularly its early days. At a certain point last year, I felt I was reliving some of that earlier trauma and also experienced PTSD. Once again, it’s a situation where people are dying and, this time, there was some discussion of it. In the ‘80s and the early ‘90s, it was sort of like we weren’t supposed to discuss it. There were stigmas, misinformation, and disinformation attached to HIV/AIDS. I started to feel: It’s happening again.

All around us, people are dying. So many of them are elderly, so many of them are Black and brown. We’ve been told by the person in power, “We’re rounding the corner; it’s going to disappear; it’s not really an issue.” I reached a point where I was thinking, “No, this is maddening. I can’t believe I’m living through this again.” And we’re still in the midst of it. I have a special feeling for other writers, especially student writers, trying to write now, because you’re being expected to turn in work and think and be and dream, in the midst of this terrifying situation. In the richest country on earth that prides itself on being a leader and a model, we have the debacle that we witnessed last year and that we’re still in now. The question is: How do you make sense of that? How do you write about that?

MNN: Well, thank you for articulating exactly what I’ve been feeling for the last year.

JK: You shared insights that people hadn’t raised before. I appreciate the questions you asked. Thank you all so very much!

About the Interviewers:

Monique Ngozi Nri

I am a Black, cisgendered woman of Nigerian and Barbadian parentage who has lived and worked in Lagos and London and now New York. I am a poet and writer who works full time in Student Services and is currently a sophomore in the Brooklyn College MFA in Creative Writing. I am committed to fighting for social justice in all areas of my life.

Peter Soucy

I was born and raised in Rhode Island and now live in Brooklyn. I am a poet and writer attending the Brooklyn College MFA and working both as a Writing Assistant at BMCC and as an Adjunct Instructor in Brooklyn College’s English Department. I am passionate about innovative writing that queers and questions the status quo and fights for social justice.

Elizabeth Hickson

I spent my childhood in rural Ohio before relocating to the American South for several years. Currently, I live in Brooklyn, where I am a second year in the MFA program in poetry at Brooklyn College. Like my fellow editors, I am committed to fighting for social justice and equity in the arts and in the world.