Patty Gone makes art about popular things. They have a strong curiosity for what makes people obsessed with Kim Kardashian or why people want to dress in all Gucci. Their work often focuses on different poles in culture and gender in the attempt to draw people toward some kind of a center.

I first met Gone in their first semester teaching undergraduate creative writing classes at Hofstra University. Though the class was slated to be taught by another professor, Gone was there in the classroom on the first day, showing us pictures of The Leaning Tower of Pisa for a lesson on perspective. They were always bringing up the idea that fiction can bring different discourses into conversation in ways that nonfiction sometimes cannot—an idea that has impacted my writing tremendously. They were also the only professor who assigned essays about cancel culture or the sex scenes in Game of Thrones.

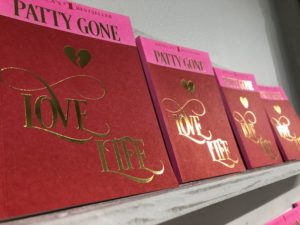

Gone’s most recent chapbook Love Life is part of their March 2019 Mount Analogue Space Residency project. They are also the author of The Impersonators (Factory Hollow Press), and director of the ongoing video serial “Painted Dreams.” Their current column “Off Brand Video” produces video pieces that trouble, queer and speak back to mainstream cultural production.

Read an excerpt from Love Life here: https://www.blush-lit.com/journal/#/patty-gone/.

I thought Love Life was really funny. Do you think humor is just a part of your voice or is it because of the subject matter you write about?

That’s me. I need to have the balance of going to those more temporary or dark places in order to set you up for the curveball. I can’t just take the reader there immediately. I think that’s my personality—that’s how I move through the world in a general sense. In the Netflix comedy special Nanette, Hannah Gadsby’s doing comedy and then cuts to more serious issues in the middle. It turned into this thing people were saying was groundbreaking. That, to me, feels like the best container to say any deep truth. I want the audience to feel jovial, and then I can drop the shit on them—drop the real-life darkness onto them.

Well, nothing is that serious after all.

There are things that are that serious. Since Love Life, I’m a little bit more in the mindset that some things are not that funny—some life circumstances are not that funny. I do feel that art is a way to communicate that level of darkness, though no one wants to sit in darkness all of the time. It’s so heavy. The way you get someone to really contemplate something is to win them over with a certain level of charm. Once that charm has done its work, you can then open the floor of the stage, and there’s this whole other layer down there. You can let that bubble out.

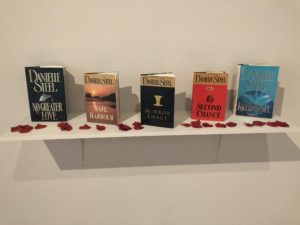

You mention that, in being a writer and in writing about authors like Danielle Steel, for example, people tend to think of you as an elitist. Is this something you’ve struggled with before?

I think it’s good to be able to dig into romance novels or other mainstream books that are not recognized on a high-art literature scale and not dismiss them immediately. I think what often happens is that, if I’m talking about these kinds of books, then there’s a trap people fall into, which is what I think the worst conceptual poetry does: points to a text such as an Amazon review, a legal document, a verbatim conversation, etc., without providing context. Then a well-educated poetry coterie judges these people. . I think this approach dismisses a whole layer of complexity regarding people’s intentions. I don’t want to come into someone else’s world in a way that just skates over that; I want to be able to come in and see what people are saying, but I also appreciate figuring out why people like a certain thing. Whether it’s books by Steel or any of the projects that I work on, I don’t want to be an elitist. I want to look through a lens above, and I also want to get on the level of the audience as much as I can.

Where did you find your way into Steel books? Your grandma has an obsession with her, but what was your way in? What made you want to write about her?

It was slow. It started when I was working on videos about soap operas called Painted Dreams and began using Steel books as props. Then, Dara Wier asked me to do a performance at the Juniper Literary Festival . I showed up with a bunch of James Patterson and Steel books and read passages to people. I used them as mystical, biblical “life texts.” I’d pick one up and find a passage. It would be totally random, but I would interpret it as if it were a passage from the Bible, as if I were reading tarot cards. I started to develop my relationship to Steel in this way, and I realized I needed to write more.

My friend Colleen Louise Barry, who runs Mount Analogue in Seattle, was working on this series of poetry and other things and asked if I would do something about poetry in romance novels. I had this prompt, so that’s why the book leans into Steel’s poetic side. Steel published a book of love poems and starts a lot of her books with poems. She’s the best-selling romance novelist of all time—the best-selling American novelist of all time —but also a poet, which I think is important.

When did you find the angle of gender binaries and feminine liberation in Steel’s books? Was that a process, or did you see that from the start of your relationship with the books?

I mean, I knew that was going to be a part of the book. I was grappling with my own trans identity. I had changed my pronouns maybe a year or two before I started it, but I hadn’t done the work of really digging into my childhood. The letters to Steel in Love Life became this place to do it, though I didn’t include them originally. The book started out as an essay about what Steel’s books do and my relationship to them.

I was riding to Hofstra on the Long Island Rail Road going through Steel books because, on the train or long commutes, they’re perfect. The chapters are fairly short, and I don’t need a really deep level of understanding; I can just skim the surface. When I would find passages that were interesting, I’d take my phone out and copy them down, so that’s where the poems came from. I was stealing and gathering lines over time. In the process, I was also reading theory, like “The Reading Process” by Wolfgang Iser, which talks about the relationship between the act of reading and the imagination.

What was really interesting to me, in conversation with friends, was talking about people’s first fantasies with their sexuality. For most of the men I would talk to, their fantasies were visual. And for most of the women I talked to, their fantasies were through romance novels or books; they were imagining rather than looking at images of pornography. I became really interested in the relationship between imagination and the written word, especially with Steel books and fiction in general as a place to generate one’s own imagination.

Were there any passages that you found in your train rides that you wish you could have included but didn’t?

I did a lot of stuff with Patterson, who is a preeminent “airport read” crime novel author, and I was going to bring that in or do a little diversion and talk about him. I think that I may do a second project or another section or sequel where I think about Patterson and what he does in culture.

I think what’s interesting with Love Life is that, for something that’s called Love Life and is about romance novels, which is inherently about love and two people getting together, it’s a very solo book. It’s very much about an individual putting themselves inside of Steel’s books as the female character. I’m thinking about what it means to be that female protagonist, but the book doesn’t delve into how I personally navigate romantic relationships.. Getting into ideas of erotic intelligence and emotional intelligence is where my work has headed since Love Life.

What are your Happy Ending workshops? I imagine they have something to do with romance and self-help?

Claire Donato and I run them. It’s an interesting place between literature and self-help. There’s a lot of conversation about what people think romance novels are, and we talk about the tropes, like “perfect lovers.” There’s a prompt, for example, that asks participants to imagine their perfect lovers. In a lot of Steel’s books, that’s what she’s doing. There’s this man who knows exactly what gifts to buy the main character. He knows what her brands are. If her previous husband didn’t want children, he wants children. Whatever the opposite of the previous lover is, he’s that. The lover becomes a solution.

In the workshop, we ask people to tell us about an actual person they have loved or had a crush on; we ask them to think about this idea of fantasy versus the actual imperfect people that we fall for. That, to me, is very fertile territory. People don’t think about it as the intersection between fiction and nonfiction, but I do. I think for those dealing with love, it’s a constant battle; you have to reckon with what you want your lover to do and what your lover actually does every day.

Now that they’re in this place between reality and fiction—how do you wrap the workshop up?

We give everyone a Steel book and read the last page. Everyone gets the feeling that I do reading them: the feeling that they are all the same. The books access a romantic utopia. I think that’s a really beautiful thing, but I also think that there are so many other ways to imagine utopia. Maybe you can meld with your community as opposed to a person who is handsome and fulfills all of your capitalist needs. So we try to push people to think about other potential romantic utopias.

What is the audience like at these workshops?

It’s all womxn: straight women, queer women, or gender non-conforming people. Zero straight males show up for any of the workshops. Only when it’s part of a class are there straight men in the audience, so that, to me, is a very interesting aspect of things. Straight men would never be caught reading a romance novel, and they’re not curious about it. Painted Dreams, the video series that is a queering of soap opera history, has had some straight males at its screenings. People drag their boyfriends to it, and afterward, they tell me they never thought of soap operas in that way. I would love for straight men to be my audience. The males in the Steel novels are these basic men who think they need to buy chic clothes for women. It’s ingrained in society to be a guy who can support his girlfriend. What’s interesting is that most men don’t even read romance novels to know what’s in them. Steel often writes emotionally intelligent men. In Heartbeat, the leading man is arguably more sentimental and emotional than the leading lady.

The guy who is a soap opera writer, right? You say he has “never inserted any 10 minute dissonant dance sequences between Acts 2 and 3 or monotonous lists into his work to give them avant-garde cachet.”

Yes. It’s good that you’re picking up on those little things. There’s a lot of those little tiny self-reflexive jokes. In that book, you’re introduced to the male character before you’re introduced to the female. He’s a soap opera writer and has this level of emotional intelligence, but men aren’t reading the book to see this man. The basic man is more interested in reading Patterson. They want a book where they can identify with a hero who is rugged and hates authority and solves crimes. That, to me, is the “basic man” archetype. In those books, the woman is a girlfriend or a wife who dies on a fairly regular basis. The male character is trying to save her, and he does sometimes. The fantasy in those books is so different from Steel’s books.

You’re very blunt and direct with ideas, calling the feminine side of the spectrum “basic bitches” in the book, and you call people basic bitches for wanting capitalist ideas. Has anyone brought that up? Has anyone been offended by it?

The idea of the basic bitch definitely comes up. My take on it is that I want to be a basic bitch—everyone wants to be a basic bitch. It’s my fantasy. My clothing at this point is along the basic bitch line. To actually be a basic bitch, you have to have a lack of curiosity, an unawareness. It’s an ignorance; it’s choosing to shop on Amazon because everyone shops on Amazon, or everyone loves Starbucks Frappuccinos, so you want to love them too. It’s channeling yourself into these things that are subscribed, and I think that to be a non-basic person, the main ingredient is to be a curious person. So I don’t blame people for being basic because sometimes it’s a class thing or it’s a lack of education. I don’t want to be judgmental of people who feel comforted by being basic—the thing that pisses me off is that Steel has the amount of money to take in more of the world and still chooses to go this route.

One thing I’m very interested in is that, as a gender nonconforming person, I have one life experience and now this second life experience, meaning that I have a working knowledge of both basic worlds, the poles of harsh masculine and harsh feminine. These poles appear in my work a lot, with the goal of drawing the audience towards the middle, towards an understanding of the side of the gender spectrum they’ve never explored.

You mention your grandma being an avid romance novel reader several times throughout the book, and you write letters to Steel asking her to sign a book for your grandma. Have you talked to your grandma about this book? Has she read it?

My sister and mom read the book. I sent it to my grandmother recently, but we haven’t really talked it out yet. I’m looking forward to that conversation. I don’t want to ruin Love Life for people, but the letters are fiction; Steel hasn’t replied to them—that’s part of the thing that makes Love Life a romance novel. There is a lot of truth and nonfiction packed into it, so it almost doesn’t matter if the audience knows the truth or not. It’s more beautiful if the letters are fiction. It’s much worse for me to say that I wrote the letters and I never heard from her. It’s better to make this a happy ending. It’s a quasi-romance between she and I. It’s unrequited over and over, but at the very end, it is requited. She gets back to me. It’s a perfect little letter where she affirms all of the stuff I wrote to her about my childhood. I don’t know how Steel feels about trans identity today. I can’t really guess because I sent her a few things and she hasn’t responded. I can’t take that silence to mean that she’s not supportive, but I can’t take that silence to mean that she is. It’s nice to dream that Steel would love what I wrote to her.