Tokyo, JAPAN – 1989

Lizzie and her cousin, Kate, were giggling like schoolgirls inside their room at Sanjo boarding house. I knocked on the door, softly at first, then louder—three virile raps. Lizzie opened the door. She was wearing pink pajama pants and a lacy T-shirt. “It’s the American.” She smiled. “Come join the fire. We’ll let you.” Kate, in business clothes, sat on the futon bed.

“What fire is that?” I asked.

“The British cultural fire. Don’t all Americans secretly wish they were British?”

“Liz…” Kate scolded.

“Well, don’t they?” Lizzie lifted her chin. “And all the Japanese want to speak British English. That’s why they pay us so much to teach at Stanton.”

Kate busied herself rearranging suitcases. She snuck a worried glance at Lizzie. Then Kate picked up a paper-back textbook. “Off to teach. Today, we’re studying Business Protocol.” She imitated a lecture: “Mr. Hirasawa, would you, like to, buy, a green umbrella?” She cocked her head the other direction to indicate the student’s response: “Yes, sank you.’”

“May, I, buy, a, pink, umbrella?” Lizzie continued.

“No. You have far too many pink items already. We’re drowning in pink,” said Kate. “See you later.” She waved and walked out the door.

“I got a new job this week, in Advertising,” I said.

“Congratulations.” Lizzie held out her hand to shake. “Now you can afford to take me out to dinner.”

“Only if there’s a good dessert.”

She didn’t answer.

“All right, we can go for sushi.”

“Sushi? Raw fish?” She groaned. “Disgusting.”

“You have to know what to order. Come on.” I pulled her arm. “I’m a sushi expert.”

“I have to get dressed first.” She opened one of the suitcases and took out a skirt. “Turn around and don’t look.”

We walked to a sushi stand near the subway station and sat out front where there were metal tables and rickety wooden chairs. “I like to eat outside,” I said. Then a taxi blew its horn and screeched past, leaving a waft of exhaust in its wake.

“Glorious,” said Lizzie.

“We’ll get the shrimp, the tuna roll—tekka maki, and the cucumber roll.” I bought the sushi at the counter and brought it back to our table. “Let’s try the tekka-maki first. It will give you a good overall sushi sensation. The fish is wrapped in rice.”

I used my key to puncture the plastic wrap on the sushi container. Lizzie’s nose quivered. She took one section of tekka maki in her fingers and carefully took a bite. She started to chew, then dropped her jaw and left it hanging open. Her face blanched — she held the unswallowed sushi at the bottom of her mouth in front of her rolled tongue. Then she grabbed a napkin, spit out the sushi, and dropped the whole mess onto the ground. “I think I’m going to vomit,” she said.

“What’s wrong? It can’t be that bad.” I took a hefty bite of the sushi to prove my point, crammed half a roll into my mouth, then shuddered as I bit into a hard fish muscle, rigid in the middle like jerky. It must have been sitting in the case all day. But I made myself swallow it anyway and held back a gag. I forced a calm expression. “A bit old, possibly.”

Lizzie folded her hands in her lap and frowned.

“Guess, it’s not too good here, huh?”

“Well, from a sushi expert, I suppose that’s a correct analysis.” There was a hint of a smile.

“We’ll go somewhere else. I know a good noodle house.” I tried to sound excited.

“No thanks.”

“Okay, we’ll go to McDonalds—or, I saw this spaghetti place near the bus stop.”

“I think I’ll just go home and have my favorite dinner.” She brushed back a stray wisp of

red hair.

“What’s that?”

“Chocolate. Lots of it. Then go to bed.”I must have smiled a little, because she continued “Alone…”

“I can’t argue too much with that logic.” I shrugged. “One of these days we’ll have a rain check.”

She stood up and walked back to Sanjo, leaving me to ponder my strategies.I sat there a few minutes trying to decide if I was still hungry, or nauseous. Then, slowly, I made my way back up the block. There was a vending machine just outside the boarding house, and I bought a can of dark Oolong. Perhaps tea would soothe my stomach. I opened it and took a sip. Because it seemed like a good idea, I bought a small bottle of whisky, also conveniently sold from from the machine, and slipped it into my jacket pocket.

Then I heard Lizzie’s voice behind me, again. “How can you stand to drink that awful tea with your Western palate?”

“So you’re following me. I thought you were supposed to be in bed.”

“I couldn’t sleep. I’m bored. How can you stand that stuff?” She shook her head.

“It’s an acquired taste… I’m bored too. Let’s—” My mind raced. “Play cards or something.”

“Play cards! You have a dirty mind, don’t you?”

“I’m very respectable. And half-English by the way.”

“Well, if you’re part British, I suppose it’s all right.”

We went back to my room and sat down across from each other on the futon. I had a deck of cards from the airplane and opened it. “What shall we play? Rummy?”

“Oh, I don’t care. Anything stupid,” said Lizzie.

“What do you mean?”

“I like stupid games. Where you don’t have to think.” She glanced around the room and stared at the jumble of clothes and magazines on my table, half of which had fallen into a messy pile; and at the mounds of Japanese coins I had left right where they fell on the tatami mat. “We didn’t have time to tidy up today, did we?” She clucked her tongue.

“I’ll show you a stupid game. It’s called Slap. Each of us gets half the deck. Then we slap cards down—up or down—by number. First player out of cards wins. It’s a matter of speed.”

I handed her half the deck. “Take out the face cards and jokers, then shuffle really well.” I

demonstrated the game with a few cards, and put them back in my stack. “Ready. Let’s start.” I turned over the first card—a 9.

Lizzie scanned through her cards, squealed, and flipped down an 8 and a 9, then another 8, 7, and 6. “Oh, this is a good game!” she laughed, and put down more cards.

I tried to play faster, flicking through my cards to find the right numbers. Several times Lizzie beat me to it and my hand landed on top of her fingers, warm and smooth under my palm. I left my hand there, just a little too long.

She got better and better at the game, until she only had three more cards, and then—”I’ve won!” she proclaimed, face glowing.

“Very good. Let’s have another game.”

“All right, but first I have to go to the bog.”

“The bog? I thought you called it the in loo in ‘English’.”

“Well, that too, but if you’re nasty, you call it the ‘bog’.”

“Are you nasty?”

“Yes.” She stood up with a little hop.

In a few minutes, she came back in, smiling, peeking around the door.

“Like the game?” I asked.

“Yes. It’s perfectly stupid.”

“You seem quite intelligent, though. I would have thought you were a Bridge or Canasta champion… Where did you go to school?”

“Ox-ford,” she said, drawing out the first syllable.

“Did you like it?”

“Hated it.”

“Then why’d you go?”

“Don’t know ’till you try, do you?”

“No, I guess not”

“—Let’s play again.”

Outside, it had started to rain, gray drops which spattered and oozed on the window panes. We played another game, but Lizzie wasn’t as happy this time. She played fiercely, thrusting her cards like knives, bending and creasing them as she placed them down. A few times I got my card down first and her hand pounded on top of it— pummeled it—hurting my fingers. “Ouch,” I said. “You know, it’s cheating if you injure your opponent during the game.”

She ignored me. “Damn it. It’s raining.”

“Just a light rain. It rains quite a bit in England, doesn’t it?”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” Her eyes flashed.

I changed tactics: “Maybe that’s why the Redcoats lost the revolutionary war with the American Colonies. Too much rain. Not enough green brellies.”

She had to laugh. “It’s brolly,” she corrected. And we kept playing cards. But soon the game was over.

“Let’s watch TV,” I said, and moved my suit jacket which was draped over a large red plastic television set on the table.

“It only gets Japanese stations.”

“Might be something interesting on, though.” The screen flashed to a commercial featuring Paul Newman walking through hills covered with wildflowers in the Japanese countryside. There was no talking, and no sound except for the rush of the wind and the chirping of birds. A company logo flashed—Japan Electric Company. Then the commercial was over. No insipid dramatized situation, no annoying announcer’s explanation, no hideous jingle—just a captivating view of nature and the company emblem. The viewer would associate Japan Electric with the beauty of nature and develop company loyalty for that reason alone.

“Why do the Japanese want all these foreigners in their commercials?” asked Lizzie.

“Want a lecture on it?”

She fluttered her eyelids facetiously. “Just the highlights, please.”

“Well at first, companies who had foreigners in their commercials were set apart. They could tame the old enemies and turn them into pets. Now there are so many foreigners, it just adds a little flair.”

“Oh,” said Lizzie, sarcasm gone.

A mock documentary began on TV, featuring a clownish Japanese “professor” in huge thick eyeglasses. He lined up five Japanese girls, naked from the waist up, then moved them until they were standing in order of their breast size, from smallest to largest. With a pointer, he poked each breast and gave a lecture on its shape in correlation to different types of fruit, whether the breast was more like a balloon or a headlight, or if the nipple pointed East or West.

“They’re really sexist, aren’t they?” said Lizzie.

I chuckled.

“Don’ t laugh!” she said.. “It’s grotesque.”

“Well—I mean, our movies have the same thing, just not on television. Except maybe your Benny Hill.”

She changed the channel again, then with a groan, turned down the volume. “You know what one of the students asked me today?” Her eyes widened. “The audacity. He asked me how come my father let me come to Tokyo? Can you believe it? I told him it was my decision, not my father’s. And that Daddy respected it. But he still gave me this skeptical look as if I were up to something very suspicious.”

I patted her knee. “Well, they just have different ideas about things. That’s all.”

“I’ll say. Medi-eval ideas.” She laughed, despite herself, and turned back up the volume on the television where a horse-faced blond American woman was bleating out a sorry, honking rendition of ‘Hey, Mr. Tambourine Man.’ Lizzie held her hands over her ears. “God, she’s awful.”

“The Japanese don’t know that, though. All that matters is her hair. Then she’s on TV.”

“—Oh, I know! They can’t get over red hair. They’ll start following me in the street, or their eyes will pop out of their heads.”

She changed the channels again, rapidly now, and finding nothing to her satisfaction, shut it off.

“We’ll play Slap again. But no hand injuries this time.”

She didn’t protest.

“Care for a drink?” I took out the bottle of whiskey,found some paper cups, poured a splash in each cup, and raised my cup in a toast. “Cheers.”

Her eyes met mine for a second, then she lowered them, and looked at me again. I thought I saw a gleam of romance, and we kissed. Soon, her mouth and jaws were reaching for me, pushing. Her hands caressed my neck and hair. We didn’t even start the game.

I woke up to a loud crash from downstairs. It sounded like someone had kicked over the shoe cabinet in the entryway. Probably a new resident. Maybe drunk. Loud footsteps ascended the stairs, and then a male began to sing loudly. Surprisingly he had a Cockney accent, replete with dropped consonants.

Not long ago, in Westminster

There lived a rat-catcher’s dau—er.

But-she-didn’t-quite live in Westminster,

But-she-didn’t-quite live in Westminster,

Now he was in the hall just outside my room. The singing continued. He trilled words together, in what seemed an authentic British folksong.

Her father-caught-rats and she sold sprats,

All-around and about that qua-ter,

And-the-gentlefolks, all took-off their hats

To-the-pretty-little rat-catcher’s Dau-er.

His singing stopped. The door across the hall was opened, shut, and locked. The concert was over.

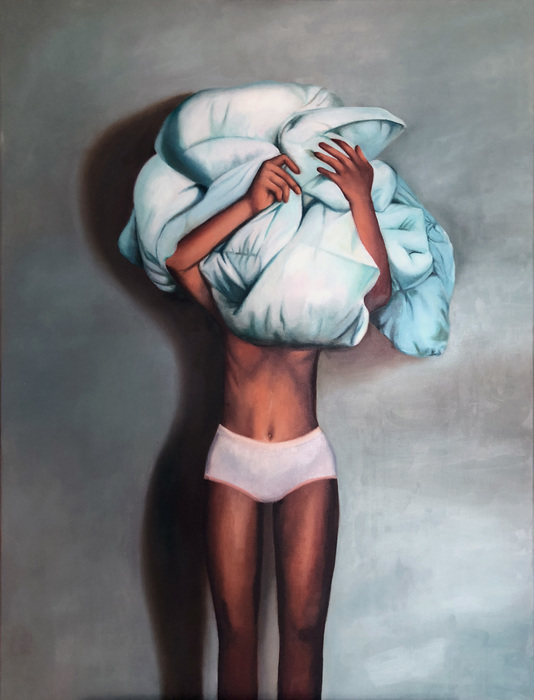

Lizzie had awakened as well. She pulled a pillow to her body, and sat up. Her red hair flowed over her shoulders. “What’s all the bloody noise?”

“One of your countrymen just moved in.”

“God, I’ll never get back to sleep. Have you any more of that whiskey?”

We drank out of the bottle.

“What are sprats?” I asked. “He was singing about sprats.”

“Oh. Little fishes.”

“Maybe good for sushi.”

She hit my leg, then kissed me. We lay down, had sex again, and fell asleep once more.

A few hours later, I woke up when I heard Lizzie’s sniffle, and a tiny whimper. I pushed myself up on my elbows. She was crying.

“What’s wrong?” I asked gently.

“Oh, I don’t know. I hate it here.”

I blinked.

“No—It’s not your fault.”

“Well, that’s good.”

She wiped her eyes with the sheet. “I miss my parents — Dad’s a minister, you know?” She twisted over on her stomach and turned to face me. “I hate Japan.”

“Why?”

“I was on the train today,” she said softly. “All alone in the car except one businessman. And he was watching me.” She touched her hair. “I looked away. Then I looked back, and he had a band-aid on his crotch—only it wasn’t a band-aid. His fly was down, and he was exposing himself.” Her cheeks tensed. Her eyes narrowed. “Next time, I’ll cut it off.” She hit the word cut hard. “I’ll slice it, with a knife–”

Every muscle in my body tensed. I sat perfectly still, conscious only of my heartbeat and breathing. “I’m sorry,” I said at last.

R. Sebastian Bennett’s writing appears in a variety of publications, including Columbia Journal, Fiction International, Indiana Review, Los Angeles Review, Oxford Magazine, Texas Review, Tulane Review, Wisconsin Review, Paris Transcontinental – Sorbonne(FR), and Alécart (RO). He was the founding editor of THE SOUTHERN ANTHOLOGY and taught Fiction Writing at U.C.L.A and the University of Louisiana-Lafayette. The story “Sprats” is from an unpublished “novel in stories,” SEASONS OF YEN, which was a finalist for the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction.