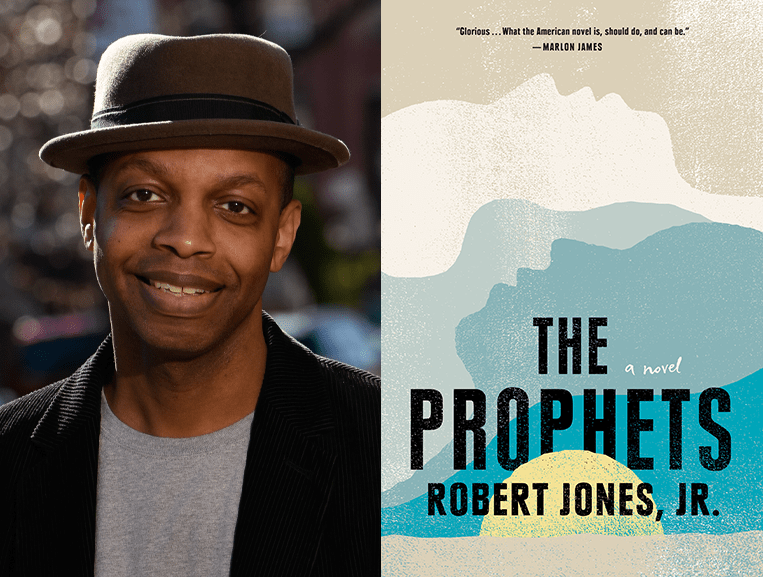

Robert Jones, Jr. is the author of The New York Times Bestselling novel, The Prophets, which was a finalist for the 2021 National Book Award for Fiction and has been translated into nineteen languages. He was born and raised in New York City and received his BFA in creative writing and MFA in fiction from Brooklyn College. He has written for numerous publications, including The New York Times, Essence, The Feminist Wire, The Paris Review, and The Griot. He is the creator and curator of the social justice social media community, Son of Baldwin, which has over 288,000 followers across multiple platforms.

Monique Ngozi Nri is a Black, cisgendered woman of Nigerian and Barbadian parentage who has lived and worked in Lagos, London and New York. She holds an MFA in poetry from Brooklyn College.

Recently, Monique sat down with Robert on Zoom to discuss writing violence in America, honoring ancestors, and the writing life.

Monique Ngozi Nri: So, let me start by asking you, like to just to dive right in: there’s a lovemaking scene between Samuel and Isaiah, I believe it’s in the “Psalms” chapter, fairly close to the beginning of the book, which I found particularly tender. I was interested in why you placed that scene towards the beginning of the book?

Robert Jones Jr: Initially, that scene came later. My agent PJ Mark thought, why be coy? Let readers know right up front what they’re dealing with here so that this lovemaking doesn’t come as a surprise, or some sort of twist that the nature of the book itself is queer. So the tenderness, the lovemaking, the sensuality, and the sexuality between these two men, Samuel and Isaiah, should come as immediately as possible. I agreed with that. This is the world that I am creating, and it should be unabashed. That was sort of the thinking behind placing that scene so early in the book.

MNN: The love story between Isiah and Samuel is the central story, but we see it through the eyes of everyone that is involved. Why did you create an ensemble cast of characters, in terms of witnesses?

RJ: Initially, I attempted to tell this story through just one pair of eyes and kept running into structural and narrative roadblocks. The story would not progress, or it was progressing in ways that were unsatisfying or uninteresting to me. And so I said, well, what is the central issue here? What is the thing that needs elaboration? And I realized it was the love between Samuel and Isaiah, and the best way to accomplish the complex view that I wanted to take on their love was to let various people see it, comment on it, and be changed by it. So, I allowed various characters to have their perspectives, the women on the plantation, even the enslavers, so that it feels like a kaleidoscopic view that is layered and complex and has depth.

MNN: I was particularly grateful for the preponderance of female or Black female voices in telling the story, because I think that in addition to the absence of the Black queer voices, there is also the absence of the Black female voice as the subject and not object, to borrow from bell hooks. I’m interested in your process as a writer because it seems to me that the book is incredibly well-researched, but there’s another piece of the magic, in terms of the lyricism of your writing, that you bring to the characters. I’m wondering how your characters are formed? How do they come into being?

RJ: Many writers have different processes. Some say go with the plot, and some say structure. When I sit down to write a story, I move from character. Like, I can’t tell a story unless I know who these characters are. So, one of the things I do is I observe human behavior very closely. So, I watched the people closest to me. I watched strangers on the street. I read many authors to see how their characters are made, but most importantly, I listened, because there is a part of the writing process that is beyond me as a corporeal being on this earth. There is something metaphysical, something spiritual about the act of writing that comes from a place that I cannot describe.

Also, in terms of the Black women characters, I was very, very close to the women members of my family: my great-grandmother, my grandmother, my great-grandmother and my grandmother’s sisters. I spent a lot of time around them, which was problematic for some people in my family because they were always like, “Go with the boys!” I found a tremendous amount of honor, grace, wisdom, laughter, and music when I was in the company of the women in my family, and I liked that energy. So, when I was thinking about these characters, particularly Maggie, I was drawing on those memories of being around those female family members to remember what a particular kind of womanhood was like, a particular kind of Black womanhood that was rooted in Southern traditions.

MNN: That reminds me of Paule Marshall, also an alum of Brooklyn College, who wrote about listening to her Bajan mum and her friends and relatives around the kitchen table, to which she credits her love of writing and storytelling. Am I right in thinking that you have some Caribbean in your background?

RJ: I do. My maternal grandfather, Alfred Benjamin, and his parents were born in St. Kitts. So that line of my family comes straight from St. Kitts. We understand that lineage on my mother’s side is Gullah Geechee, which isn’t really considered the Caribbean because it’s so close to the United States. Still, I can’t tell the difference between a Bajan and a Gullah accent.

MNN: Definitely. I’ve heard you speak about the different kinds of Black people. I’m one of those people who was born in England. My father is Nigerian, and my mother’s Bajan. I’m married to an African American. When I saw one of the ancestors in your book say soon to come, I thought perhaps you had Caribbean ancestry. And then, in the first chapter “Judges,” when the ancestors first appear, they say, what is this? I could hear the cadence of my father’s Igbo in that. If that’s an intentional use of these vernaculars, why was it important for you to include these?

RJ: Yes, my husband was born in England, in Hackney, of Jamaican, Bajan, and Antiguan descent. I am a second-generation African American. On my father’s side of the family in particular, you can trace our roots all the way back to slavery. So, I am an African American, but I realize how rich the experience of being an African American is because I grew up in Brooklyn in the seventies. I grew up in the projects, and in my building, we had Black people from Panama, Belize, Jamaica, Haiti, England, and Toronto. I never felt like this distinction, and we just knew we were Black. And we knew that we had some cultural differences, but they didn’t matter. So, when I was crafting The Prophets, it was important for me to highlight the connections between us in ways that were seamless. If you’re a close reader, you’ll see Caribbean influences, you’ll see continental African influences, Central American Black influences, and African American influences. That’s wholly intentional because, for me, Blackness is an umbrella term for all of us, though there are forces that are trying to pit us against one another. I reject those.

If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.

Toni Morrison

MNN: It was a delight for me, for example, to see the word “oyibo”, which is what they used to call my mum when she went to Nigeria. But speaking of othering, I wanted to ask you about the use of the term “toubab” because I feel that, in a way, it’s turning the tables. I don’t know if that was the intention, but it felt like a bit like othering the whiteness, so to speak. I wanted to ask you about the feedback you’ve gotten from using the word, toubab.

RJ: I specifically used toubab, which is a Wolof word, because of its indigenous meaning, which is “to convert.” And so the Wolof people were really clear about what white people, Europeans, and Christian missionaries coming into their spaces were doing to them. They were trying to convert them into something else. And so that word has so much meaning because now when we say toubab, we know that it means white, but the root of the word is to convert. And what it does in The Prophets is to show how these people are trying to convert human beings into beasts of burden, into tools, into something less than human. When these enslaved characters get to use that word, it’s almost like an act of power because they get to name what’s happening to them and what these people are doing to them, and also understand themselves as people; that they are not slaves, they are enslaved. That they’re not this thing, but that it is something that is being forced upon them or something that is being done to them. And so I found that word to be so subversive, and I love the use of it. I haven’t received any negative feedback for that, but I did receive a lot of questions about why this word is in particular. And then once I explain why I use this word, people seem to find it empowering. That has been pleasant to discover.

MNN: Yes, I was interested in these spaces you create for the enslaved characters, or maybe they created them for themselves, to have these tiny pieces of resistance. I’m thinking of Samuel smiling while he’s being forced to drag the wagon naked around the outskirts of Empty, or Puah in her alternate universe. There are just these moments that I find so rich, but I was struck by the almost casual way with which you depict depravity and violence.

RJ: One of the things going into this that I realized was that slavery was another word for violence, so it had to be treated as a normal part of the slavery landscape. Every time I was writing about particular acts enslaved people had to do, or about life on that plantation, violence was always foremost in my mind. I also realized that America is also synonymous with violence. We normalize everyday acts of violence as almost virtuous—war, police forces, military forces, disciplining our children, all of these things are violent. In this country, violence is normal. It’s almost like saying this is the way human beings are supposed to be. So, in crafting this book, I kept all of those things in mind. This country was formed out of violence, and it is embedded in even the constitution of the country, so I didn’t want it to be extraordinary. If I’m writing about America, violence has to be ordinary.

MNN: Is the story designed in some way to shake the reader out of their complacency about these assumptions?

RJ: I would say that foremost in my mind when writing The Prophets was that I wanted to read a story that I haven’t read yet. Toni Morrison said if you cannot find the book you wish to read, then you must write it. I had never seen Black queerness addressed during this particular time, or in pre-colonial Africa. I realized that what I was writing was against a particular point of view that queerness comes out of the corruption of the Black person, that it is a result of the traumatic encounter with Europe, and against the idea that the reason Black queer people exist is because we were sort of corrupted and distorted by the European imagination. When my research began, I started to discover that actually, what was true was that Europe came in and saw African societies that embraced queerness and transgender people and all sorts of expressions of the human spectrum, then demanded that it stop, and did so through the use of Christianity, Islam, and violence. I guess one of the side effects of The Prophets is that it provides an education about the Black queer person’s place in human society. That was not my goal, but I am glad that the book can function in that way, that it can educate people who may not have known that homosexuality, or being transgender, lesbian, or bisexual is not a corruption. It is a normal part of human existence.

MNN: It took 14 years to write the book, in part because you had to stop at times. I have to tell you that I had to stop, not because your book isn’t beautiful but because, as a child of war, I don’t put myself in front of violent things, if that makes sense. Some writers are able to witness such horror and maintain their sanity. So, I wanted you to enlighten me on that subject.

RJ: It was an extremely grueling process, and here’s the thing about antebellum slavery in America: as gruesome as parts of The Prophets are, it was worse in the research. I found even worse examples of the brutality, the cruelty, the inhumanity, and the violence. What I present in The Prophets is pared down from what I actually found and still, it’s a lot. It took me 14 years to write it because when I was writing the violence, I could feel the pain at the tips of my fingers. I would have nightmares about some of it. I had to think about separating myself from it because sometimes it felt like it was happening to my own body.

What kept me going was me saying to myself, Robert, if the violence is hard for you to write, imagine how it must’ve been to experience it. And your job is to witness, right? You cannot turn away. At some point, you find a shield that protects you from it. And I think that’s the ancestors telling you, I’m going to give you a little bit of a buffer so that you can tell my story because it has to be told. So, my way of bearing it was trying as much as I possibly could to find the inner resistance of those characters, the beauty of those characters, and to sort of press up against the violence that they were experiencing. And that was the only way I could make it through. And it, and still, it took me 14 years.

MNN: Were some of your primary sources? Were you at the Schomburg?

RJ: I was lucky enough to be Africana studies minor at Brooklyn College in my undergraduate years. I had a stack of books about the slave period in the United States and in Brazil, and on the Middle Passage that I used to place myself. So, when I was writing scenes, I could rely on second-hand memory. Sometimes, I would write something and then I would say to myself, is this accurate? You know, does this have some research basis, or did this spring completely out of my imagination? And if it is made up, is it all right for me to do that? Then I would go back and check sources and realize that it was not far off. I’ve internalized so much that I can trust my own memory of these things. So that is how I dealt with it, because a lot of people will read my book and wonder, did this actually happen? And fiction doesn’t rely on that question because, as Toni Morrison said, fiction is not fact, but it is truth. Sometimes, facts can obscure the truth. So, I let myself be as imaginative as I could be in that journey.

If I’m writing about America, violence has to be ordinary.

Robert Jones Jr.

MNN:I had a question about magical realism, the spaces that particularly the enslaved Africans seem to move in and out of. The way that you deal with nature and light and shadows and all of those pieces, even the practice of voodoo, all of those things that are outside of the material sphere—I was very taken by those moments. I wanted you to talk a little bit about that layer of the novel.

RJ: For me, what I was trying to capture—I don’t know if I would call it magical realism because I’m writing in a tradition where there is no border between what is called magic and what is called real. It is all a part of the grand experience of being alive. My grandmother used to put a glass of water under the bed if we were having nightmares. She would put salt in front of our doorsteps so that nobody evil could cross into the house. She kept a chicken claw in a glass of water on the sill so that there could be no lies told in her home.

So, these things were normal. There was no action that was considered strange or magical or whatever other word; that was just what it meant to be a loving protector of your family space. It was how my grandmother showed love and how she, in ways that she wasn’t even aware of, passed on things to us. If we combed our hair and didn’t burn what came out, she would have a fit, you know? All of those things are a part of who I am as a person. So, I wanted to make sure that my experience of being a Black person showed up in my world. I guess in the literary sphere, they have a term for that. They call it magical realism, but I just call it life.

I’m writing in a tradition where there is no border between what is called magic and what is called real.

Robert Jones Jr.

MNN: Speaking of the literary world, I was laughing to myself that you said at 30 you would be the old one in the class. I was 62 when I went back to get my MFA. There are all kinds of discussions about folks going into MFA programs versus not doing that, so I wanted to ask you about that experience and what you think it gave you in terms of your craft.

RJ: I did have a great deal of insecurity about returning to school as a 31-year-old because in my head, I should have been in college at 18 and graduated at 23, 24, whatever the age is when you’re supposed to “graduate.” But I realize that had I gone to school at 18, I would not have known what I was there for. It would have been a waste of money and time because I did not have the level of maturity required to do the work and understand exactly why I was there and what I wanted to get out of it. So, I’m glad that I went back later.

In terms of the MFA program, it was a really interesting experience because—how can I say this diplomatically?—as a Black student in an MFA program where Black students are not the majority, you are often seen as an adversary to the white people in that program. They are constantly attempting to get you to write in ways that are comforting to them. But oddly enough, you always find those one or two other students or instructors who understand what those dynamics are like and try to shelter you from them and keep you encouraged in writing the way you want to write.

I was lucky enough to find someone like Ernesto Mestre at Brooklyn College, who mentored me a great deal. And there were three other Black students in that program with me, although they did a really good job of keeping us separate from one another in the workshops. I never had a workshop with another Black student the whole time I was in that program.

The danger of being a Black student in an MFA program is that people in power will do everything to prevent you from writing in ways that might be deemed uncomfortable or offensive to your white colleagues on what we’re seeing in the United States right now, with this backlash against critical race theory. What I would say to a Black student going into an MFA program is to steel yourself, because you will be going against the tide plenty of the time. You know why you’re there, and you will have to protect yourself and be resilient against those attempts.

As a Black student in an MFA program where Black students are not the majority, you are often seen as an adversary to the white people in that program. They are constantly attempting to get you to write in ways that are comforting to them.

Robert Jones Jr.

MNN: I would concur so much. I went to the Brooklyn College for my MFA because I wanted to be able to say, “I know my craft, I’ve studied this thoroughly.” But it was shocking to me that there were almost no people who look like me either teaching or in the program. Talk a little about Baldwin, who I believe you discovered at college.

RJ: I came to James Baldwin rather late in my life. I was introduced to his work in my freshman year of college at the age of 31 in a class entitled People, Power, and Politics. I read a work by him called Here Be Dragons. I was so taken up by that essay. I’d never read anything like that, where someone is so astute and intelligent. And then I found out that he was Black and queer and lived in New York City. I immediately adopted him as my spiritual godfather, and he really is the person who taught me how to write. He let me know the things that I wanted to write about, and that it was okay to be polemical when it was called for. He gave me the courage to write from a Black queer perspective. I could not have been the writer that I am today without James Baldwin.

MNN: In the parts of The Prophets that depict pre-colonial Africa, I was wondering whether those scenes came out of a particular place, or wether they were an amalgam of ideas, or totally imaginary?

RJ: I’ve been to South Africa. I went to Johannesburg and Cape Town. That’s significant because South Africa was the first country in the world to give LGBTQ people constitutional protection. It came out of the sentiment that no one shall ever be oppressed in this country again, after what we’ve experienced. It was Black lawmakers who made that decision. I’ve always had a fascination with the continent because I know that I am descendant of it. On my father’s side of the family, we could actually trace all the way back to Guinea and Burkina Faso. My name is Robert because the first Robert, all the way back those many generations ago, did not survive the crossing from England, where he was purchased by a family named Habersham, to Savannah, Georgia, where my father’s people are from. His younger brother named his firstborn son after him. His name was Robert, and every firstborn male in my family down to me is named Robert.

And so that connects me to the continent. So I’m always fascinated with the ways in which various African peoples think about the world in terms of politics, in terms of culture, music, dance, religion, spirituality, sexuality, and such. And so I did a lot of research about that and found that various places all over the continent had such different ways of thinking about human existence.

So, the Kosongo people that I fictionalized are pieces of all these things that I discovered about African indigenous thinking, set up in a way so that it can be a strong contrast to the Western European ways of thinking. So, while there are no Kosongo people, it is true that African peoples had women kings. It is true that queer people were considered guardians of the gates by the Degara peoples, and so all of these aspects are based on truth. I just combine them in this one community for the purposes of the narrative.

MNN: So, who are “the Prophets”?

RJ: Everyone in that book. The purpose of a prophet is to give us information about a better way of living, and to warn us of the things that we’re doing that are going to lead us to catastrophe. And even the slave master, Paul, is a prophet because he shows us the ways in which we can give up our humanity for material things. Each of the characters in the book, whether enslaved or slaver, the people in the African village—they all have vital information for us about ways to live in which we are not harmful to one another, or to the land, so that we can finally live up to this idea of humanity, an idea we so often fall terribly short of.

MNN: You surround yourself with ancestors, and I was also struck by the strength of your communities. For example, the Brooklyn College seems to have a great affection for you. And you seem to be out in the world with community in terms of your Sons of Baldwin blog. I’m going to leave you with this question, and I don’t know if you could necessarily answer it, but I wondered what you feel you’ve learned in the journey to publication and beyond?

RJ: Community is incredibly important to me and I am grateful for the people who have become like family and who become part of my tribe in this journey. I don’t know any other way to be. I’m following the elders in my family who create a community wherever they went, too. I have made tremendous friends of other Black writers who have embraced me. I turned toward the people who want to be in a relationship where we’re supporting and rooting for one another. So that has been wonderful. The lesson I have learned, from starting in this book in 2006, publishing it in 2021 and then seeing the aftermath, is that all that really matters is that you get your testimony out into the world. How it’s received—whether or not it wins awards, whether people love it, like it or hate it—has nothing to do with you. You have created an artifact that will outlast you, that people may be reading for generations to come. You have added something to the human tapestry that no one can ever take away, no matter what they do or say. That is all that matters. What matters is that I got an email from a young man in Kenya who told me he got my book on the black market, and it changed his life. That’s what matters.