“No one is who they say they are, not even myself,” reflects performance artist Tamar Tumanishvili halfway through Jonathan Garfinkel’s funny and wild debut novel, In a Land Without Dogs the Cats Learn to Bark. Tamar is about to begin a three-day bus ride from Istanbul to Tbilisi in order to investigate the mysterious past of her mentor, academic Rachel Grabinsky, whose recent death has led Tamar to reassess both Rachel’s identity and her own. It’s an enigmatic phrase, one repeated by various characters throughout the book, including Rachel’s son Joseph Grabinsky, who writes it in a notebook while in pursuit of Tamar, and Daniel Daniel, a Coltrane-obsessed record store owner moonlighting as Joseph’s Tbilisi tour guide.

The refrain also speaks to the makeshift nature of Georgia’s capital city Tbilisi in 2003, a dozen years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, where much of the novel is set, and evokes the novel’s examination of shifting identities. Following a raucous cast of characters in settings ranging from Moscow to Toronto to Tbilisi, and including car chases, run-ins with the KGB, and hunting mishaps with real life presidential candidate Saakashvili, the novel offers multiple entry points into a country difficult to pin down. Part spy-novel, part historical fiction, the deeply funny and at times unsettling novel interrogates the duplicity of the Soviet Union, the role of art in acting as a truth-teller, and the lies we tell ourselves in order to survive.

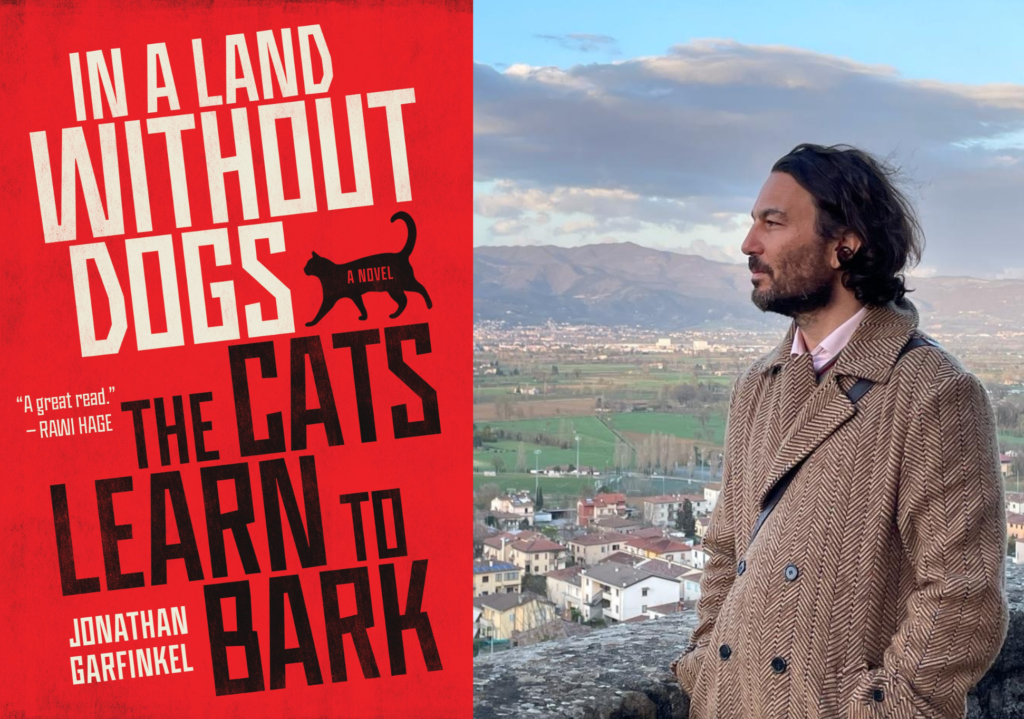

I caught up with acclaimed playwright, poet, memoirist Jonathan Garfinkel over Zoom, where we touched on experimental theater, post-Soviet politics, and the shifting identities at the heart of his novel.

Cassidy McFadzean: We met in Tbilisi in 2018 when you were teaching as part of the Summer Literary Seminars. You’d previously been to Georgia as a playwright and an artist. Could you talk a little bit about what initially drew you to the country and how you began thinking about the Caucasus?

Jonathan Garfinkel: The truth is I didn’t know anything about the Caucasus before I went in 2002, which was a long time ago and a very different country and a different region. I went because of my mentor at the time, Paul Thompson, a theater director in Toronto, who was one of the pioneers of Canadian Collective Creation and helped start Theatre Passe Muraille. I had been working as a playwright with him on a few projects and one day one night we were at a party, and he started talking about the Republic of Georgia and saying he’d been there in the 90s because he used to run the National Theatre School of Canada. He was in Moscow to explore different directing techniques, and he had ended up in Tbilisi because the Russians all admired Georgian theater. While he was there, the Civil War broke out, so he only got to see one play before being shepherded out of the country. It was a very chaotic time, but he said he’ll never forget that play, and he always wanted to return because he believed there was such a strong tradition of theater, and so he asked me if I’d be interested in going with him on a cultural exploration.

Tbilisi in 2002 was a very chaotic place, as was it in 2003 when I returned with the company of actors and worked at a theater there in a cross-cultural exchange. But it was a total free-for-all, like the electricity didn’t work, there was rarely running water, the corruption was mad, and there were no tourists at the time. It was considered a failed state, but the people I met were incredible, and the theater I saw was beautiful and very moving, and I fell in love with the place.

CM: I was struck by the amount of research that went into the book, as evidenced by the many organizations and individuals you thank in the acknowledgements as well as your trips over the past 20 years. Could you talk a little about what went into your writing process?

JG: It was not a quick process as you gathered. I was unsure about how to write about it because I’m not Georgian, but it was a place I couldn’t stop thinking about and wanted to write about, in part because not a lot has been written about it in in English and every time I wanted to read more about Georgia, I always felt like there was something missing. But falling in love with a place is a weird reason to write a whole book. I needed to find my way in, which ended up being through the politics, the people and the history, and every time I kept returning, I found different levels of meaning to the place. I went back in 2008 just before the war with Russia and then just after the war, and already things had started to change. I’d been there before and during the Rose Revolution and then went back in the 2010s, and then the last time I saw you there, in 2018, it had changed quite a bit but still, retained its amazing charm and bizarre energy.

In terms of the process, at first it was sort of accidental; I just was curious, and I wanted to learn more about the place and people were more than willing to talk about it. I would say by 2008 I knew I was going to write a book of some sort, but I wasn’t sure if it was going to be a travel book or a memoir or a novel. In 2008 I went back, and I spent time with Human Rights Watch, which was really interesting. I really liked interviewing people, I liked seeing and smelling the places, and then of course, reading whatever I could get my hands on, which wasn’t always a ton. I got to spend time with the woman who Tamar is based on, Nino Sekhniashvili, and it was really interesting hearing about her art practice.

I’m not a big reader of historical fiction, that’s the funny thing, but it became a historical political novel and as I got deeper into it, I felt it compelled and a duty to try and understand as much as I could, with respect and humility for a place that is pretty hard for an outsider to understand.

CM: The book begins in Moscow with Chechen character Aslan trying on American Gary Ruckler’s Wrangler Jean jacket and throughout the book, different characters repeat the enigmatic phrase, No one is who they say they are. So much of the book is about shifting identities, family secrets, what we inherit from the past. How do you feel the book taps into those layers of identity in post-Soviet countries such as Tbilisi?

JG: Before getting to the post-Soviet, I would say that there’s something about Georgia that I found interesting, which is the difficulty to grasp identity there even though people were so sure of who they were. People were just so proud to be Georgian and declarative of their Georgian-ness. I mean, it is an ancient culture, it’s an ancient language, and yet there’s something about trying to pin down what that was that was always elusive. You can say that about any place, I suppose. What does it mean to be Canadian? What does it mean to be American? We always come up with these dissatisfying narratives and mythologies about what a nation is, but I found it very interesting because I’d never been in a place where people were so proud of their nationality.

When I dug into the history, I found that it’s a history of occupation. It’s always been occupied by other empires. So, the Soviet occupation for them was just one of many, in a way. Before that it was the Russians, the Ottoman, the Persians, and what I always found interesting was the way they’d integrated aspects of all those cultures while maintaining their own. So that sense of shifting identity was something that didn’t seem to really bother them. It just seemed to be part of their reality.

And if you watch Georgian theater, they have a very interesting relationship to death that I felt very compelled by. There’s a famous theater director I mention in the book, Robert Sturua. His most famous play was Caucasian Chalk Circle, a production of Brecht. But I also saw a production of Hamlet in 2002. And I’ll never forget, it was all in Georgian. In fact, there was no heat in the big Rustaveli theater. The Russians had turned off the gas and when a character in the play died, there was a way their ghosts lingered on stage that felt visceral and real, and it was a very prolonged death exit, where you would feel the presence of that person even in their passing. There’s an attitude towards shifting identity—even between life and death— that people were less threatened by. That they seemed to embrace as a culture.

I think in terms of the politics it resonates quite a bit in terms of people trying to formulate a new sense of self. I guess that’s part of one of the big questions of the book for me: how do you emerge from 70 years of Soviet totalitarianism and change that mentality as a nation and as an individual?

CM: I’m thinking of the character Daniel Daniel, who is trying to give directions to Joseph, and says, “Houses do not have numbers and streets only sometimes exist. In the Georgian state, we are very much an existential problem.”

JG: That’s a good way of putting it. In a way, the example of Georgia and the post-Soviet is very extreme. Other countries weren’t quite as extreme in terms of the violence and the chaos, but Georgia really devolved into an extreme situation. We’ve seen this with Ukraine as well young post-Soviet nations grappling for identities. And I mean young in the sense that they’re newly independent with long histories and long senses of identity as nations and cultures, and with language and all the rest. But to have the vault of communism suddenly end and then having to learn how to become a democratic country, and a capitalist country was shocking, and very much so in Georgia with the old regime and the old power still there. There’s a reason why they called the 90s generation the lost generation.

What compelled me when I went in the early 2000s was that there was a sense of openness to the country, like it could go anywhere, it could be anything. But I wasn’t living in that chaos, and it must have been very hard for many people. It was as Nino the performance artist said to me, a very special time, and a time of great inventiveness because people didn’t have much. Not to be nostalgic, but it was really interesting. I remember seeing a puppet show of Faust, and there was a power failure in the middle of the show so that the whole theater was thrown into darkness. The actors just calmly lit a bunch of candles, and they held candles for each other and finished the play by candlelight. It was just absolutely beautiful.

CM: There’s a lot of humor in the book, especially in the character of Aslan, Daniel Daniel’s emails to Joseph Grabinsky, and the scenes with presidential candidate Saakashvili. It’s also a book that contends with the Russian occupation, intergenerational trauma, and horrifying scenes of violence. Why was it important for you to capture both the really deeply funny and the tragic?

JG: Personally, that’s just that’s something as a playwright I’ve always enjoyed. Tony Kushner talks about starting his plays off with a few jokes to warm up the audience so that it opens them up to the darker stuff. I mean, Kushner does that very well. Having spent a lot of time in post-Soviet countries—I’ve lived in Lithuania for a time, I lived in Hungary as well, even though it wasn’t the Soviet Union, it was Communist, and then Poland, Ukraine, Georgia, and so on—I think people endured the horrors of these places through absurdity and humor. You need a kind of humor to survive. As a writer of Jewish descent, that’s part of our tradition in a way, surviving through ghetto humor and all that. So for me it’s something that’s quite natural but also conscious in the sense that you need a good sense of humor to survive the kind of darkness of the intergenerational trauma that people went through.

CM: The book is in many ways a spy novel with car chases, KGB, and references to Raymond Chandler. There’s a tension that seems to stem from constant surveillance. These characters inhabit a world where people can’t live without being observed, watched, or followed. Could you speak to the role that surveillance, or the spy novel more generally plays in your book?

JG: Going back to your question of identity, even in the sense of living in a state of surveillance for as long as people did during the Soviet Union was an important thing for me to consider as an important psychological aspect of people’s ways of looking at the world. I’m not even a huge spy genre reader, but I got intrigued by the idea of everybody basically being duplicitous in one form or another, so it’s a book about lies and it’s a book about people lying to each other, changing their narratives, changing their sense of who they are often for reasons of survival— in fact, it’s almost always for reasons of survival.

I think that’s true to the history of the Soviet legacy, and it’s also a hell of a lot of fun to write, so the spy genre speaks to that in a very direct way, though I took liberties with it. As I was writing this, I did go through a phase where I was reading quite a bit of Raymond Chandler, and even some Jean le Carré—some of his books are quite brilliant—and I like playing with that form because it also spoke to that question of duplicity very, very well. And then of course imagining what that would look like if there was some humor to it. I think the book plays with a whole bunch of different genres. It asks existential questions. There’s a lot of humor in it, and there’s elements of the spy and the noir, but I like the idea of trying to find ways where they all could meet, and it does go back to your question of shifting identities. It was a device that let me take that subject and theme deeper.

CM: I would be remiss if I didn’t ask about the classic Georgian scenes in the book: the Supra (Georgian feasts led by a speech master), hunting scenes, as well as some allusions to the street gangs. These are all pretty masculine spaces, but at the same time you have female characters like Rachel Grabinsky and Tamar, and queer character Davit, who are hugely important to the book’s plot. In what ways did you want to capture the macho culture of Georgia, as well as subvert it?

JG: As you know, Georgia is a very macho culture, but Tamar, Davit, and Rachel allowed me to explore the other side of that. I met people like Davit and Tamar there, but it’s complicated, you know? Traveling there as a man who has never hunted, never picked up a gun, who’s diabetic and shouldn’t drink so much, it’s a pretty weird and uncomfortable place to be thrown into, and I found myself in these kind of situations that really challenged my own question of who I am as a man or what being a man really is. I certainly never thought it was important for me to hunt. As a Canadian Jewish guy, that’s not in my world, but I found it fascinating because it challenged my sense of masculinity.

I also was very interested in the flip side of that because there are people like the Tamar character who have to live with it and who are deep thinking, creative people who have to find ways to express that in a way that does not put them into total danger all the time. And then someone like the Davit character, who was loosely based on a news personality who was shot in the late 90s for corruption he was revealing about the government, who was living life as a gay person in a very homophobic society. I thought that they were interesting flash points to the question of masculinity. I think what it allowed me to explore were extremes of gender identity and have them speak to each other.

CM: You’ve already touched on the vitality of the art scene and the theater scene, but that’s what struck me when I was there, the sense of creativity and inventiveness, which you capture mainly through Tamar’s role as a performance artist.

JG: I really enjoyed inhabiting that part of the book. I was nervous about it. I’m not a Georgian woman and nor am I a performance artist, but through all the research and people I met, I enjoyed what it allowed me to try to explore about that aspect of the post-Soviet, what art means in a place like that, and it seems a lot less frivolous to me when you’re dealing with art as a means of survival.

Everybody’s trying to survive in different ways and Tamar’s trying to survive through her art, which is a kind of truth telling, which is an interesting counterpoint to the duplicity of the preceding generation. So, I think in some ways Joseph and Tamar and Davit are all trying to speak to the duplicity of their parents and grandparents. That’s the legacy of the Soviet Union they’ve inherited, and in questioning who they are, because it really is a book about questioning identities: Who was my mother? Where was she? Why did she change her name? In countering the Soviet experience, they’re hellbent on some kind of truth and honesty.

CM: One of the book’s many delights for me personally came from recognizing some real-life places such as the apartment on Ritsa Street in Tbilisi, where we were neighbors. How did you determine which real spaces you wanted to include, or you want your characters to inhabit, and which you wanted to invent, such as the record emporium and the Underground Theater, which is a blend of the two?

JG: The record store is a fictional creation. Most of the other locations were based on real places. The Underground was based on the Basement Theater, which was also called the Sardapi, which doesn’t exist anymore. I mean, there’s a version of it, but not in the same place. I think that I always started with a real place in mind that I had been to and then embellished. It became a question for me of what I could make a living breathing space, and I didn’t really have any hard and fast rules except when it came to historical moments, like the Rose Revolution, I tried to describe things accordingly based on those truths and the massacres in 89, but in terms of the space, I guess they’re all kind of hybrids, to be honest. The record store is probably the most fictional because there is no record store like that in Tbilisi but that was based on something I had seen in Vilnius, Lithuania, which is quite a different place than Georgia.

I would say that I drew very much on my experience of physical spaces. Physical space in general really was an important thing for me in terms of my research, whether it was going to Pankisi Gorge or hanging out with Nino and her partner in the countryside and hearing about the way she made things. I spent an afternoon with photographer Guram Tsibakhashvili in his studio and as much as I loved looking at his photographs, it was his socialist apartment that most affected me. So it was his shaky apartment that Daniel Daniel lives in. I got things from all these different places, but I couldn’t have done it all just by sitting at home and looking at a book or videos or whatever. Having done some journalism in my life, I started with the real and then hybridized it, if that makes sense. I mean, fiction allows you to kind of do whatever you want when it comes to physical space.

CM: Is there anything I’ve left out that I haven’t touched on that you want to talk about?

JG: I could say one more thing, just in terms of working on the novel for a long time and just feeling I was writing about a very obscure place that nobody really cared about, and then suddenly while I’m doing my copy edits, the war breaks out in Ukraine was a very interesting experience.

Not that this is a book about Ukraine, but I think there are some resonances in terms of the struggles of a country like Georgia. Many people would like to join the EU or be part of NATO, or at least these are things that are talked about quite a bit. To have this suddenly become a bit more on people’s radars has been an interesting experience. It was less of a far-flung exotic place and more of oh, we’re all part of this in some way. I don’t know what that does to the relevance of the book, but it certainly was interesting to go from a sense of being isolated and writing it, and then suddenly to be out in the world.

CM: Yeah, like contending with this new context or this spotlight?

JG: Exactly. It suddenly became internationally relevant in a more explicit way. I was always intrigued and fascinated by these young movements of people wanting to become more western and more democratic and their particular struggles that they’ve been up against in the post-Soviet context, with what they’ve inherited from their parents directly and then politically what they’ve been accustomed to. I found those challenges really interesting, because I think we’re at a time where we in the West are questioning our institutions and how strong and relevant our democracy is and how effective it is, and how that even is supposed to work with capitalism, if it even works at all with capitalism, which it probably doesn’t.

And so, to talk about the Rose Revolution, for example or even the Maidan in Ukraine in terms of groups of people who want to join the West. I have an ambivalent relationship to our democracies and capitalist structures. But then when you think about what they’re gone through and what they want, I found that interesting. That’s also why I wasn’t trying to have the Rose Revolution be this idealized, Oh now Georgia is a democracy, and everything is fine. I mean, of course it’s not. Everything’s not fine, and I imagine by the time people finish the book, they’re not going. This is a happy ever after story. We’ve gotten rid of the old communists and put in a Pro-American leader. It’s not happily ever after. It never is.